Do You Know Your Full-grain from Your Bovine Splits?

Do you ever wonder why some leather-goods last longer and age way better than others? There are many reasons of course, but one of them is undoubtedly the quality of the leather. You may have noticed that we describe our leathers as ‘full-grain’ – here we discuss just the difference between a ‘full-grain’ and a ‘split leather’ or ‘bovine splits’.

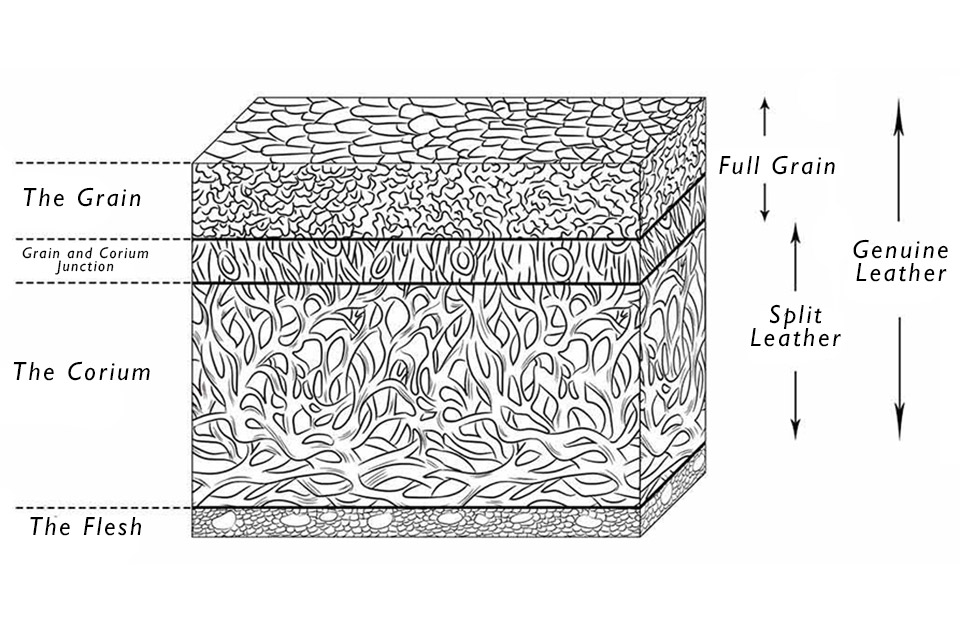

The explanation lies first in understanding the layers of the leather itself. As a raw hide, the whole thickness of the skin is comprised of three key layers. On the inside, the ‘Flesh’ layer has quite a tight structure of fibres, making a strong inner skin for the animal. The middle layer, which forms the greatest thickness of the hide, is the Corium. The fibres in this layer are more disorganised and open in structure – it’s purpose in life is to be the superhighway for supplies for the skin, and to provide thickness and a cushioned barrier for the animal. The upper layer of the hide is the bit we see on the outside, it carries the hair follicles and protects the animal from abrasions and drying out – the fibres are tightly knit to provide a really resilient surface – it’s called the Grain.

Not All Leather is Equal

Having established these layers, it’s fairly reasonable to expect that full-grain leather should retain the full Grain of the hide, and it does. You might think all leather does, but that’s where it gets tricky, because not all leather is full-grain leather. In fact, an awful lot of leather is not, especially the leather that is used to make bags. And the retail price is not always a fair guide to the quality of the leather used.

The Leather Splitting Machine

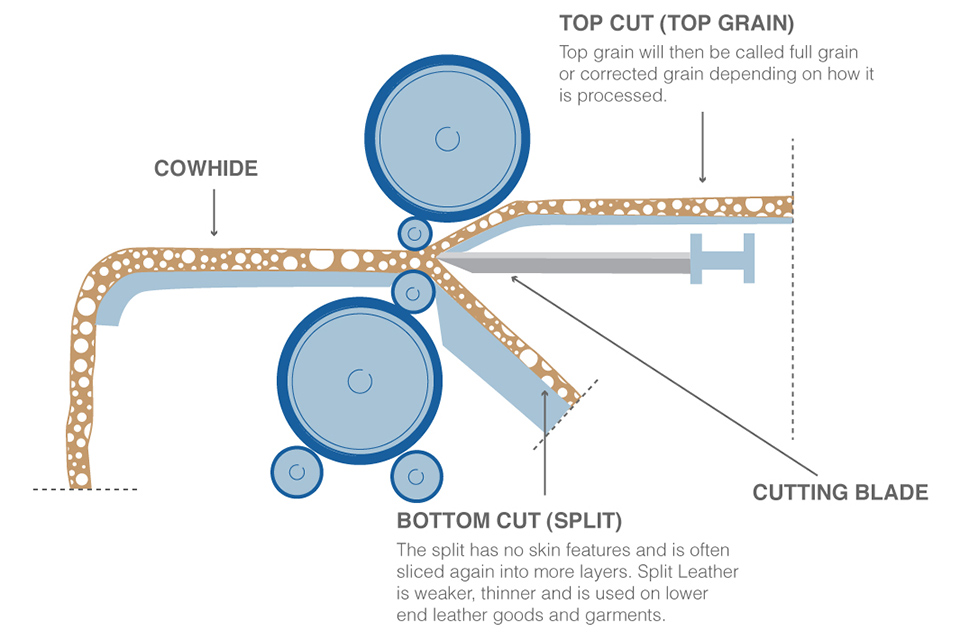

This is because the thickness of the original hide is such that it can actually be split into two useable layers. With the aid of a fearsome machine called (maybe a little unimaginatively) a Splitter, leather can be divided along its horizontal plane, in effect peeling the top from the bottom, giving two full, just thinner, pieces from the first. The layer with the Grain becomes the ‘full-grain leather’ and the remainder becomes the Split.

Satchel Leather

The invention of the splitting machine gave us a whole new way of being more efficient with our hides. Prior to this, the grain was always the focus, and leather was thinned by hand by progressively shaving off ultra-thin layers from the back (flesh side) with a very sharp blade – in much the same process as planing wood. The splitter revolutionised this slow and painstaking process, but also gave us ‘split leather’, or in the case of cow hides, ‘bovine splits’ (which is not, as it turns out, an advanced yoga pose for cows).

The splitting machine cuts beautifully, giving a super-flat surface to the back of the full-grain piece and on the new ‘top’ of the Split. The Split can now also be used as leather, but there is one key difference – without the grain, it is much more fragile than it was. Lacking the tight fibre structure of the grain layer, the split leather is now much less resilient and can tear easily, so it must retain a reasonable thickness to be useful. However, its new top surface can be extensively treated to improve its appearance.

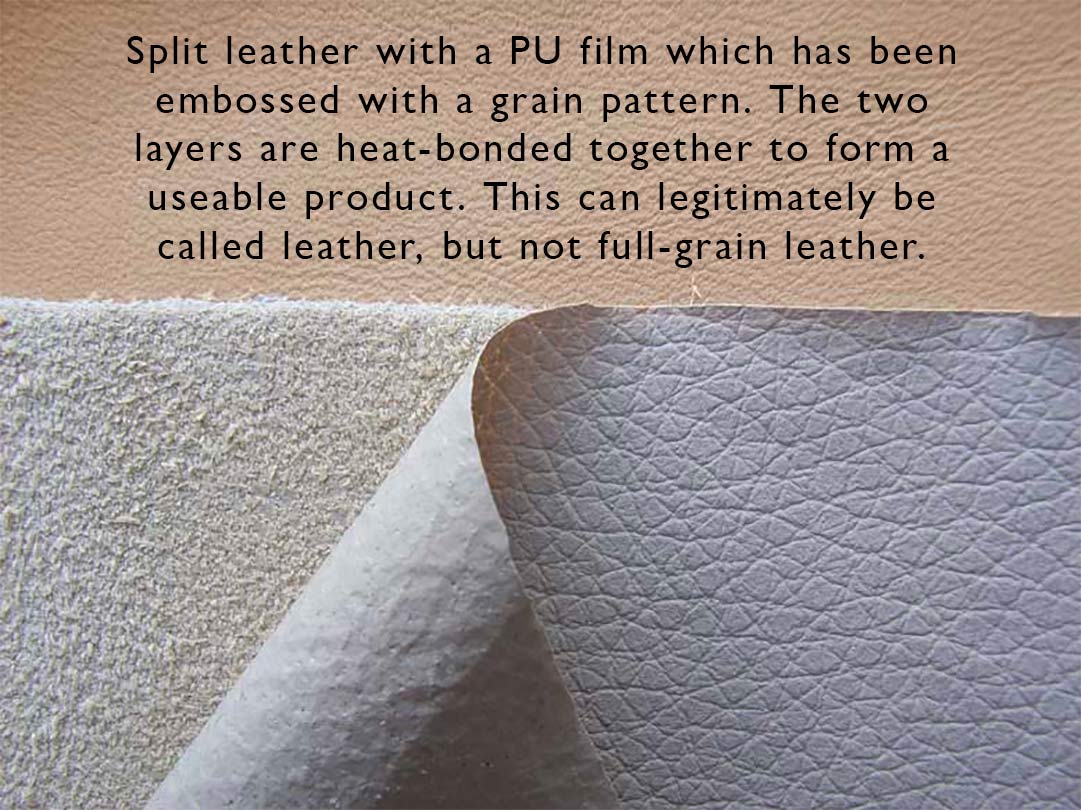

By coating it in a thick layer of pigment, or, more typically, a plasticised paint or polyurethane (PU) finish, which can also be embossed with a grain pattern, the Split can be made to look almost exactly like full-grain leather. The emergence of the electric splitting machine gave us the first mass use of these splits – in school satchels – back in the 1950s, every schoolchild had one. Nowadays we see everything from this ‘satchel leather’ to extremely convincing saffiano or croc-prints that are almost indistinguishable from the real thing – but only when new.

This same process of PU-coating is also used to ‘correct’ poorer quality skins which, whilst not fully split, have their uneven full-grain surface buffed off before being coated, and also perhaps grain- or pattern-embossed, to create a totally uniform surface. This is a method used to extend the usability (and increase the price) of poorer quality skins, where there may be flaws in the grain which are consequently masked by this ‘correction’.

Corrected leather, therefore, whilst still in possession of some of its surface grain (and therefore some of its strength), is fully covered up and will also not polish and patina as natural full-grain leather can. In this image, it is possible to see the greater definition of the grain in the natural leather (on the right) and the more ‘filled-in’ appearance of the coated grain on the left.

Resilience and Character

Given that these coated and printed Splits can look so good, what would be the problem in using them? Well, as with so many things in life, quality tends to come to the fore, even if it takes a while. The far greater strength and flexibility of full-grain leather allow it to yield to movement in all directions and yet rebound and recover its shape with no damage. And the more natural the finish on such leather, the more it will polish and patina with use over the years. Split leather, on the other hand, will be less flexible and its surface can’t patina – instead, it is more likely to peel or wear off, progressively losing its newness but without replacing it with character as a full-grain leather will.

Additionally, full-grain leather can be split down to less than a millimetre and yet still retain amazing tear strength whilst becoming as soft and pliable as a fine fabric. This is essential in the making of fine leather-goods which require the leather to be skived very thin where the layers overlap, in order to achieve the desired finesse in the quality of the manufacture.

In this video, Gillian Tusting demonstrates the use of the splitting machine in the Tusting workshop and shows how different full-grain leather is from split leather.

We are always very happy to answer your queries regarding our leathers, so if this article has sparked a question for you, please do not hesitate to